The entourage effect: Does it really exist?

Mind & Matter is a monthly column by Nick Jikomes, PhD, Leafly’s Director of Science and Innovation

The entourage effect is the idea that two or more drugs can act synergistically when consumed together, stimulating effects that would not be observed if they were taken on their own.

Cannabis-derived products typically contain more than just THC. Consumers often report that cannabis products offer effects not readily explained by THC content alone. Research has suggested that pure THC is not as well-tolerated by medical cannabis patients as botanical extracts. This has given rise to the notion of entourage effects in cannabis: THC is the main driver of psychoactive effects, but these effects can be modulated by other molecules. As a result, different forms of cannabis might have distinct effects depending on the specific ‘entourage’ of chemical compounds they contain.

The idea has captivated scientists and consumers, but is it true? Is there any clear evidence of entourage effects among any cannabis-derived cannabinoids and terpenes? Or between THC and other types of drugs?

What about psychedelic entourage effects among the various species of psilocybin mushrooms, which are also known to vary in their chemical content?

Related

The entourage effect: How cannabis compounds may be working together

Known entourage effects with cannabinoids

Early evidence for possible entourage effects with cannabinoids came from studies in the 1990s.

Led by Dr. Raphael Mechoulam, they looked at the endogenous cannabinoid 2-AG, which interacts with the body’s two main endocannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2. Scientists found that 2-AG was often present with other endogenous compounds, some of which could enhance 2-AG’s physiological effects in mice. This showed that ‘entourage effects,’ where one or more molecules enhance (or diminish) the effects of another, may be one way the endocannabinoid system is regulated at the molecular level.

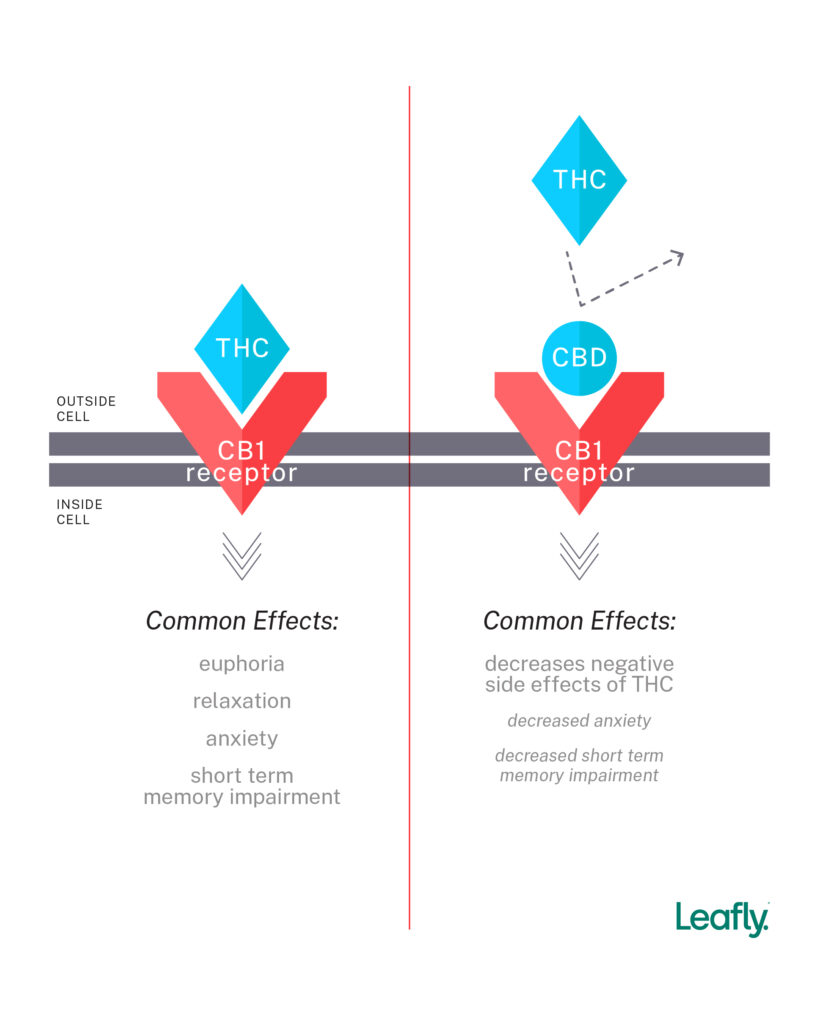

One example of an interactive effect between two cannabis-derived cannabinoids is THC and CBD. THC activates the CB1 receptor of the endocannabinoid system, accounting for its psychoactive effects. CBD also interacts with this receptor but in a different way, changing CB1 such that it changesTHC’s ability to activate it. This probably accounts for CBD’s ability to mitigate some of THC’s side effects, such as paranoia and short-term memory disruption.

CBD mitigates the direct effects of THC

Studies have shown that the THC:CBD ratio also influences the level of psychoactivity experienced by cannabis consumers. For infrequent cannabis consumers, when CBD is present at much higher levels than THC, intoxication is reduced compared to THC alone. Conversely, consumption of THC (8 mg) together with half as much CBD (4 mg) enhances the intoxicating effect, but only for infrequent consumers. In people who frequently consume cannabis, the intoxicating effects of THC don’t change much when combined with CBD. This indicates that the psychoactive effects of cannabis can change based on the THC:CBD ratio in a way that depends on your level of consumption experience.

There may also be entourage effects involving the impact of cannabinoids on pain. Full-spectrum cannabis products can show better efficacy and tolerability for pain patients compared to pure THC. The details still need to be worked out, but cannabinoids like THC may have interactive effects with opioids. Animal research has shown that when opioids are combined with cannabinoids, pain relief can be achieved using a lower dose of the opioid. More human clinical research needs to be done here, but synergy between cannabinoids and opioids may be one reason why states with medical cannabis laws tend to see reductions in the use of certain prescription drugs.

Entourage effects between cannabinoids and terpenes?

Are cannabinoids the only factors in entourage effects? Maybe not.

There is speculation that terpenes, the volatile compounds that give cannabis its aroma, can modulate the psychoactive effects of THC. One of the most influential scientists popularizing this view is Dr. Ethan Russo, with whom I’ve spoken about cannabinoid-terpene interactions:

Two of the more widespread beliefs about cannabinoid-terpene entourage effects are:

- Limonene provides antidepressant effects, brightening the effects of a THC high.

- Myrcene provides calming or sedative effects, accounting for the couch-lock phenomenon many THC consumers are familiar with.

While intriguing, these claims tend to rest on thin evidence. In humans, the evidence is almost entirely anecdotal. There is no clear clinical evidence in humans that limonene or myrcene modulate THC’s effects in these ways, although clinical trials are now underway to assess this.

While there is some preclinical evidence that terpenes like limonene and myrcene may have psychoactive effects in animals, these studies typically involve injection of terpenes directly into rodents, at doses that may not resemble those seen with human cannabis consumption, and without co-administration with THC.

Myrcene is one of the most common cannabis terpenes. It’s not uncommon to hear that it promotes sleepiness. There are some animal studies investigating myrcene’s effect on sleep, but they involve injecting rodents with myrcene together with drugs like pentobarbital, a barbiturate with strong sedative effects. The results have generally not been replicated and sometimes show contradictory results, even within the same study, depending on the details of each experiment. While there may be good reason to expect that some cannabinoid-terpene entourage effects will be discovered, research to date is too sparse to draw firm conclusions about human cannabis consumption.

Related

How might terpenes contribute to the entourage effect of cannabis?

Private research also being done

There is more data out there about cannabinoid-terpene interactions. Unfortunately, it’s owned by private companies who are unlikely to share it publicly. For example, I recently talked to Dr. Andrew Chadeayne, who ran R&D for a Colorado-based company called ebbu, Inc. (Ebbu was purchased by Canopy Growth Corp. in 2018.) Researchers at ebbu apparently did an exhaustive set of experiments looking for interactive effects among the major cannabinoids and terpenes found in cannabis. For example, they measured whether any terpenes enhanced or diminished the effects of THC at the CB1 receptor. Apparently some terpenes were able to significantly enhance THC’s ability to activate the CB1, which would be expected heighten its psychoactivity.

Cannabis and other plants communicate with the external world using the language of chemistry, but we are only just beginning to decode the meaning of this language. It will take years of study to understand what this chemical language means for human medicine and human experience.

“I like the piano analogy,” Dr. Andrew Chadeayne once told me, “where it’s like you’re not just playing one note but playing different notes. You start making chords. It’s this multifactorial sum of the pharmacology that creates the experience.”

Terpene function and entourage effects in nature

One hint that terpenes may participate in entourage effects is that plants, fungi, and other organisms produce specific terpenes to serve their ecological needs. There are many examples. Sometimes a single terpene performs one clear function. Some plants (including certain cannabis cultivars) produce β-farnesene when attacked by aphids. Acting as an aphid “alarm bell” pheromone, it causes the pests to stop feeding and disperse. (Cannabis growers take note: if you’re having an aphid problem, consider growing something with high β-farnesene levels). There are also examples of synergy. Some potatoes, for instance, produce two similar antifungal compounds, with the antifungal effect of one boosted by small quantities of the other.

It’s also notable that plants like Cannabis tend to produce cocktails of terpene molecules in specific ratios. The fact that different “strains” expression distinct terpene combinations likely reflects that each descends from a particular lineage of plants adapted to a specific environment. Some specialize in defending against aphids, others against powdery mildew. The plants are playing chemical chords, not individual notes. A key step toward defining any bona fide cannabis entourage effects is therefore the map out which terpene entourages are reliably found in commercial cannabis.

Entourages in high-THC cannabis

Scientists at the University of Colorado-Boulder and Leafly recently partnered to map the cannabinoid and terpene content of commercial cannabis. The results of this study elucidate the most common combinations of cannabinoids and terpenes found in the products used by consumers. If there are any robust cannabis entourage effects, we should be able to observe them through careful administration of the cannabinoid-terpene combinations associated with real products, at doses resembling naturalistic human consumption.

THC-dominant cannabis, containing little or no CBD, makes up ~96% of the commercial market for cannabis flower today. People just don’t buy very much high-CBD flower.

Among commercial THC-dominant samples, are there distinct entourages–combinations of cannabinoids and terpenes–that reliably show up? The answer is yes. In our study we used unbiased clustering algorithms to parse samples into statistically distinct groups based on their chemical phenotype (chemotype). We found that there are at least three distinct chemotypes of THC-dominant cannabisreliably present across US states.

What are they? Below are simplified summaries of each chemotype of high-THC cannabis, together with some additional information relating each one to popular industry labels, including Indica/Sativa and strain names. Listen to this talk for a deeper dive.

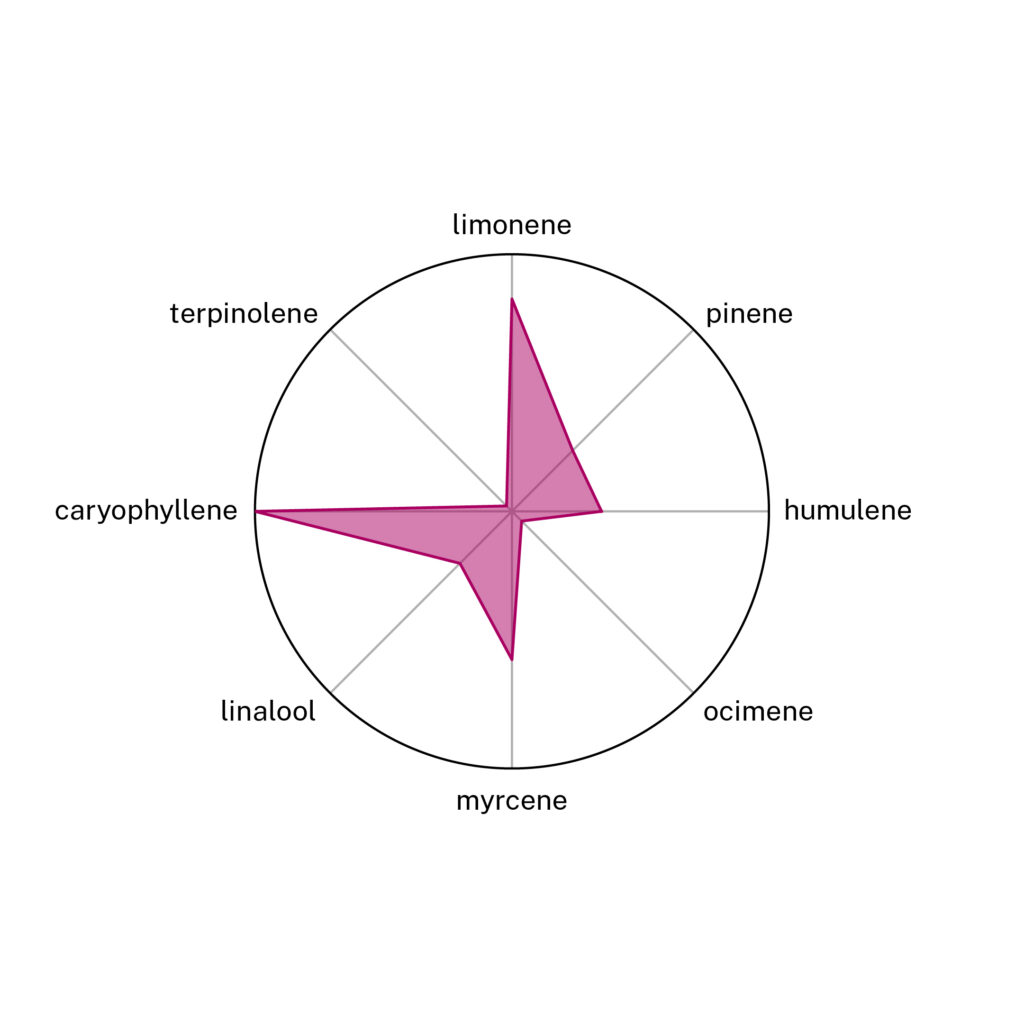

- Chemotype I–High β-Caryophyllene + Limonene. These samples account for ~53% of commercial THC-dominant Cannabis and have relatively high levels of the terpenes β-caryophyllene and limonene together with a mix of other terpenes. This chemotype was not preferentially associated with samples labeled “Indica” vs. “Sativa.” Strain names such as “Glue,” “Cookies,” and “Cakes” were among those over-represented for this chemotype.

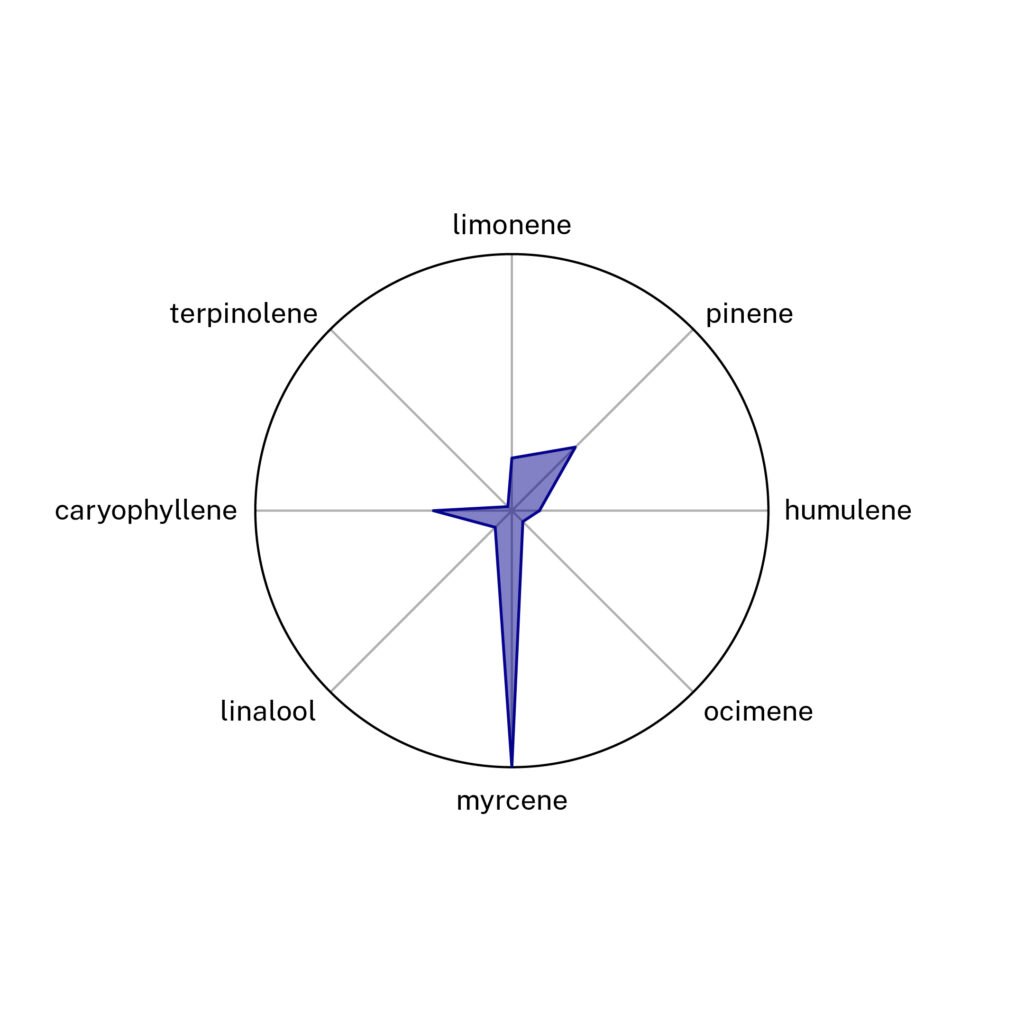

- Chemotype II–Very High Myrcene + High Pinene. These samples account for ~34% of commercial THC-dominant Cannabis, having relatively high levels of myrcene and pinene. A popular example of a strain name over-represented in this chemotype is Blue Dream. Again, there was no clear bias for these samples to be “Indica” vs. “Sativa.”

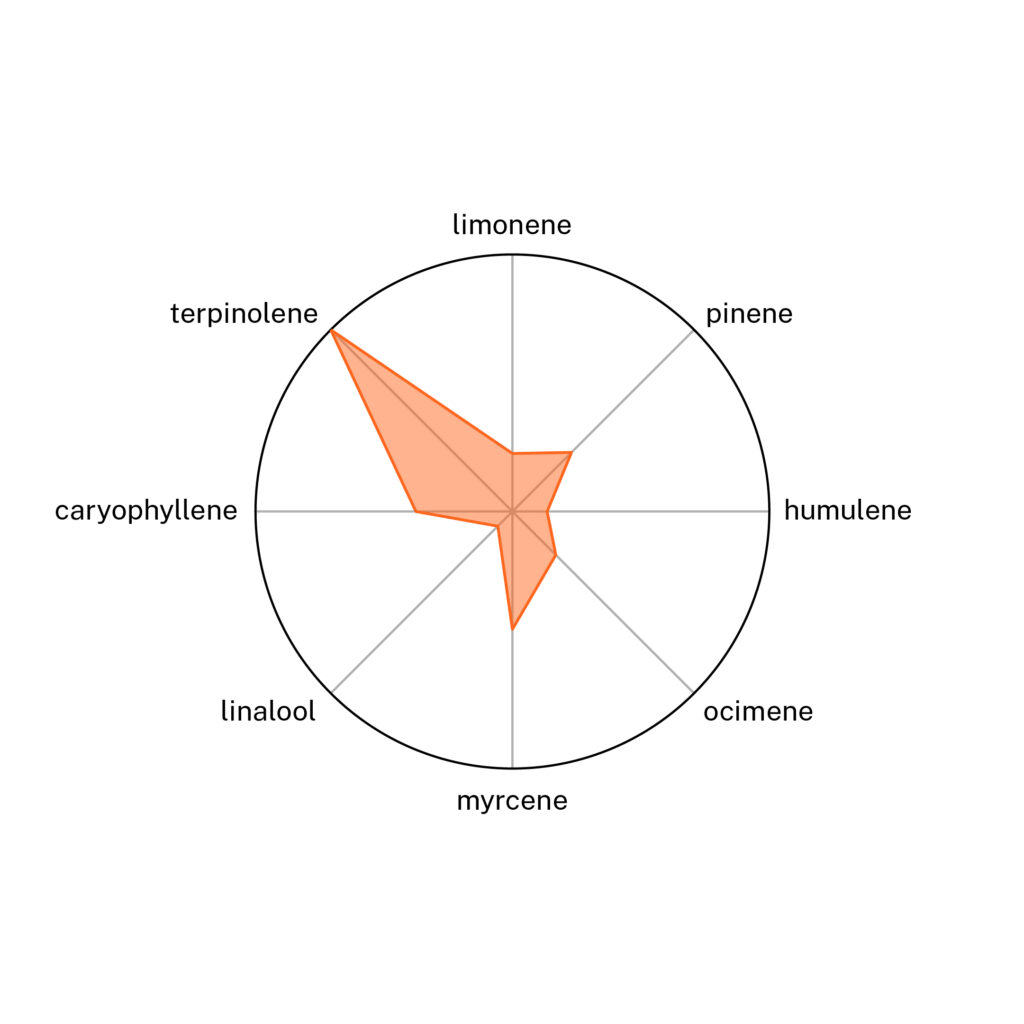

- Chemotype III–Very High Terpinolene + High Myrcene + Ocimene. These samples account for just ~13% of commercial THC-dominant Cannabis, with high levels of terpinolene. This profile is associated with mild levels of the cannabinoid CBG, at ~1% on average. Intriguingly, samples labeled “Sativa” were over-represented in this group, which came from a small subset of “Sativa” strain names, e.g. Lemon Haze, Jack Herer, and Dutch Treat.

While some of the chemically-defined groups can be further split into sub-groups, these were the three chemotypes of high-THC cannabis most reliably present. In other words, they represent different entourages of cannabinoids and terpenes–ones that consumers are encountering with high frequency among commercial cannabis products. Do these entourages offer distinguishable psychoactive or medicinal effects? We don’t know. Someone needs to measure this in carefully designed, properly blinded, dose-controlled studies.

Potential entourage effects in psilocybin mushrooms

Cannabis is not the only biological entity with the potential for interesting entourage effects. Psilocybe mushrooms are also of interest. Like cannabis, one drug accounts for most of its psychoactive effects: psilocin, the active metabolite of psilocybin. Also like cannabis, different species and strains contain different ratios of psilocybin and other compounds.

In addition to psilocybin and psilocin, Dr. Andrew Chadeayne told me about lesser-known alkaloids sometimes present: Norbaeocystin, baeocystin, 4-OH-tryptamine, norpsilocin, aeruginascin, 4-OH-trimethyl-tryptammonium. We know very little about these, although he did share an interesting anecdote about the mycologist Paul Stamets, who has consumed pure baeocystin:

Some Psilocybe mushrooms also contain compounds called β-carbolines, which are monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Pharmaceutical MAOIs were once a common prescription for depression but are rarely used today. Plant-derived MAOIs, which typically lack the dangerous side-effects of pharmaceutical MAOIs, are found in many plants. In fact, β-carbolines are one of the two key ingredients in ayahuasca. The other is the potent psychedelic alkaloid DMT, which is only orally active when taken together with MAOIs.

The presence of β-carboline MAOIs in some Psilocybe mushrooms is interesting because they might influence the metabolism of psilocin. The presence of MAOIs is expected to intensify or extend the duration of a psilocin trip, although this still needs to be formally demonstrated.

Are there other potential psychedelic entourage effects, involving different combinations of fungal alkaloids and MAOIs, which we might discover among the various species of magic mushrooms? It’s entirely possible. Psychedelic startups like CaaMTech are chasing these questions.

The current task for researchers interested in entourage effects, for both cannabis and magic mushrooms, is to map the entourages reliably present in nature and commercial products. From there, we must carefully measure whether distinct combinations offer unique psychoactive or medicinal effects.

There is still much work to be done before we crack the chemical codes of these organisms.

To learn more about Mind & Matter and listen to the podcast episodes that inspired this article, visit this link.

Nick Jikomes, PhD

Nick is Leafly’s Director of Science & Innovation and holds a PhD in Neuroscience from Harvard University and a B.S. in Genetics from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the host of a popular science podcast, which you can listen to for free at: www.nickjikomes.com. You can follow him on Twitter: @trikomes

View Nick Jikomes, PhD’s articles

By submitting this form, you will be subscribed to news and promotional emails from Leafly and you agree to Leafly’s Terms of Service and Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe from Leafly email messages anytime.

Post a comment: