Legal Cannabis Is Producing More Plastic Waste Than Pot

Since 2018 legal weed in Canada has been a source of pride and prejudice for consumers and non-consumers alike. While there is much to love about legal weed in Canada, there is no question that there is room for improvement in the industry.

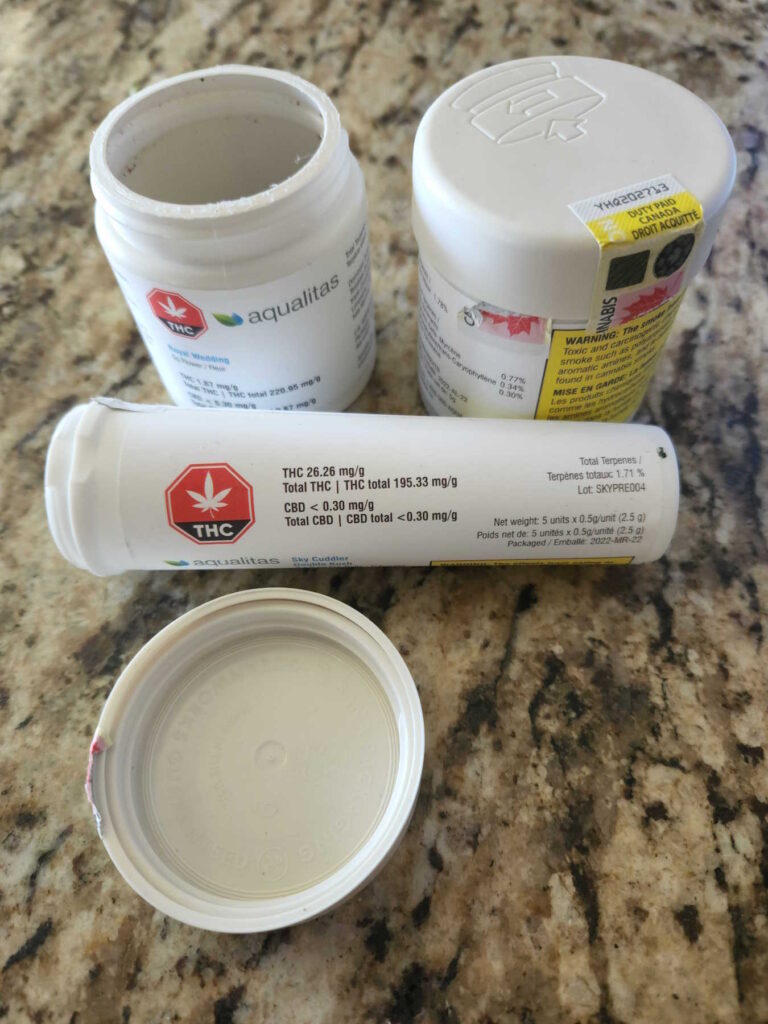

Perhaps one of the most obvious and overlooked is one to which many suppliers contribute, but few have made genuine strides to mitigate: the millions of pounds of plastic packaging for legal pot.

In the early days of legalization, solid black plastic packaging dominated the market, with many brands opting to package their product in sleek-looking but unrecyclable containers.

These jars are widely used and decompose slowly over decades, pumping toxins into the soil and eventually making their way to the closest ocean. The exact scope of the rec market’s plastic waste problem is hard to quantify, but the overall impact has been decidedly negative.

In 2019, the environmental company [Re]Waste estimated that between 5.8 and 6.4 million kilograms (or between 12.7 million and 14.1 million pounds) of plastic from cannabis packaging ended up in landfills between October 2018 and August 2019,

And cannabis sales and the range of available products have only increased since then.

A widely circulated CBC report, published only five days after legalization came into effect, found that for each gram of cannabis that was legally sold, as much as 70 grams of plastic waste was generated.

Cannabis packaging-derived waste is a complex problem involving the entire industry—from regulators and producers to consumers and the growing number of players purporting to chart a more environmentally-friendly way forward for the nascent industry.

Some companies have made genuine progress on the plastics issue, and industry-wide efforts to promote implementing the use of recycled materials and encouraging consumers to recycle containers have steadily, albeit slowly, gained steam.

Blaming the regulations is tired, but they definitely don’t help

Cannabis packages must be opaque or translucent, child-resistant, include a security seal, and be large enough to accommodate a label that includes a significant amount of information (including a large warning label) in both English and French, all with minimum font sizes.

All of these directives contribute to increasing the amount of plastic that goes into the containers. This limits packaging options for producers and pushes companies toward using low-cost plastic containers.

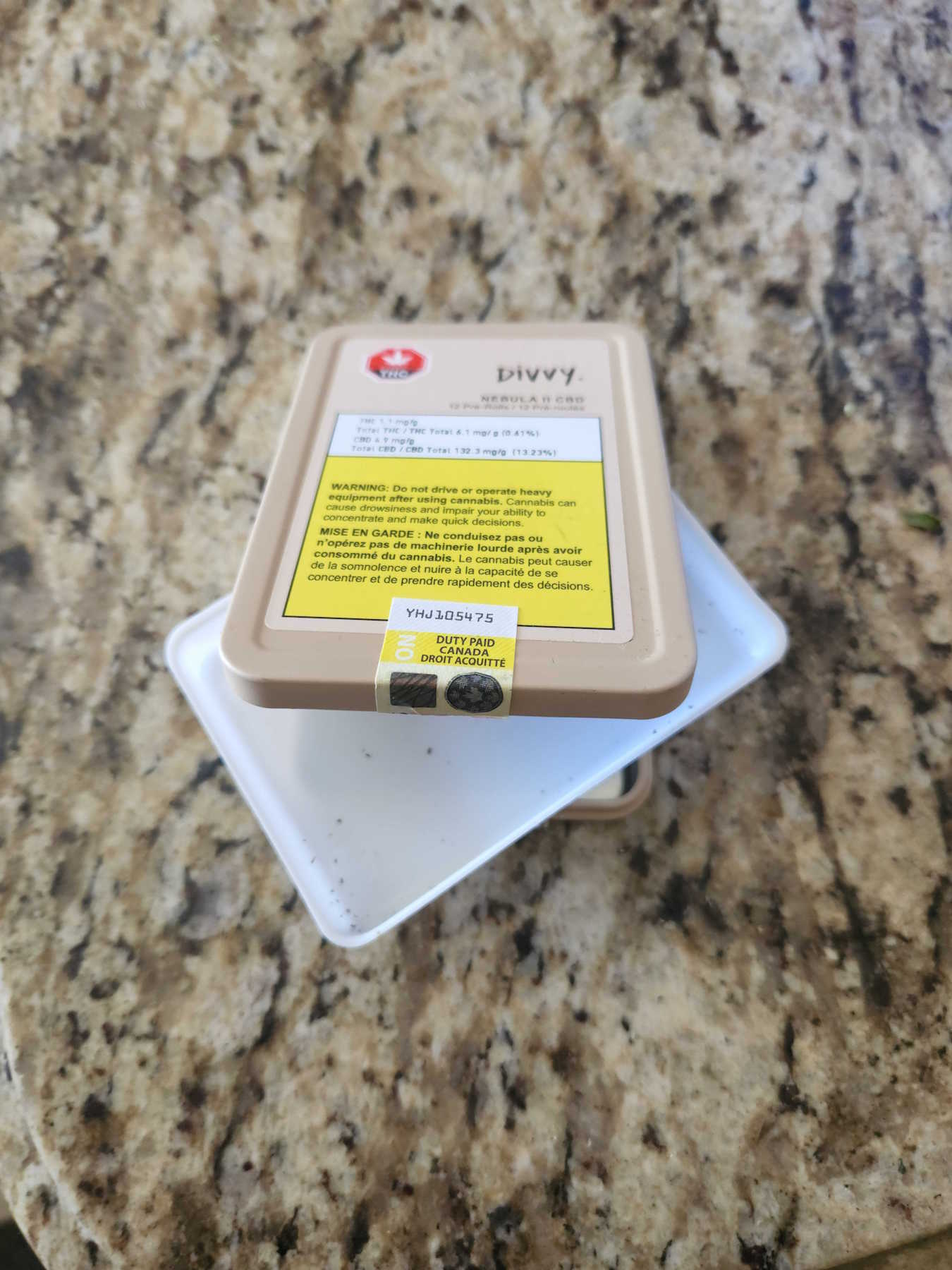

Some companies, like Divvy, minimize their plastic use with tin and removable parts. (Keenan/Leafly)

Health Canada has argued that they don’t force these companies to use the cheapest option; officially, the organization “encourages the use of innovative and environmentally sound packaging approaches, provided the requirements in the regulations are satisfied.”

But meeting those requirements is nearly impossible to do without the use of plastics, especially for producers who also want to ensure the freshness of their products.

Polypropylene plastic, a thermoplastic “addition polymer” manufactured by combining multiple propylene monomers, became an obvious choice for the industry from the outset.

In a regulatory compendium, the Canadian cannabis packaging supplier CannaPack wrote that “the unique properties of this material ensure it can keep cannabis dry and free from contamination given it has an excellent vapour and moisture barrier.”

It’s also light, sturdy, and recyclable—all things cannabis producers look for in their weed jars.

“When you build those Venn diagrams, there’s only so many packaging options that you can have,” says Grant Caton, general manager for Canada at Canopy Growth. And deploying packaging at scale compounds the issue.

“You tied that into your production facility, at scale—hundreds of thousands of bags going through a machine,” Caton notes. ” All those things need to line up to make sure they work.”

Myrna Gillis, CEO of Nova Scotia-based craft producer Aqualitas, notes that fear of running afoul of Health Canada’s stringent packaging regs is a motivating factor in maintaining the current, waste-generating status quo.

“They really don’t turn their mind to that at all,” Gillis explains. “They leave those decisions to the producers to make, but if you don’t do it in a way that’s compliant, then there are consequences.”

Health Canada takes the position that its role is to craft regulations with regards to public health, as opposed to environmental impact; sustainable packaging falls outside its purview.

| Brand | Product | Packaging materials | Can it be recycled? | Can it be composted? |

| 48North | Pre-rolls | Cardboard, soy-based ink | Yes, in standard blue bins | Yes |

| San Raphel | Live resin concentrates | Polypropylene + Glass | Yes, in standard blue bins | No |

| Truro Cannabis | Bubble hash concentrates | Tin can with plastic lid | Yes, in standard blue bins | No |

| Reef Organic | Dried flower | Reclaimed ocean plastics | Yes, in standard blue bins | No |

| Good Supply | Oil cartridges | PET plastic bottles | Yes, in standard blue bins | No |

| Mood Ring | Vape cartridges | Hemp plastic mouthpiece | No | Yes |

| Kolab Project | Pre-rolls | Paper carton | Yes, in standard blue bins | Yes |

| Ghost Drops | Dried flower | Glass | Yes, in standard blue bins | No |

| Tweed | Dried flower | Mylar bags | Yes, but only through a specialty program | No |

| UP Cannabis | Dried flower | Plastic (Dymapak) | Yes, but only through a specialty program | No |

| TreeHugger™ | Pre-rolls | Hemp, bamboo, and cardboard | Yes, in standard blue bins | No |

A McGill University 2020 study of the industry’s plastic waste found that “cannabis regulations—grounded in concern for public health and public safety—have led producers to package products in larger and more resource-intensive containers than necessary.” The study’s lead author, Omar Akeileh, is now the director of partnerships and sustainability at the Cannabis Council of Canada.

“Excessive packaging is a result of designs that must accommodate large standardized labels and excise stamps, regardless of the packaged contents’ volume,” Akeileh writes in the study.

As a further complication, Health Canada also heavily restricts cannabis advertising– gagging companies who are packaging more sustainably from promoting their position and preventing waste-conscious consumers from making informed choices.

“With no way to communicate to customers whether their packaging is environmentally-friendly, some producers may find it difficult to justify moving away from inexpensive virgin plastic,” the study states. “Taken together, cannabis producers are risk-averse and have few incentives to explore innovative packaging solutions.”

Producers are leading sustainability efforts

Despite restrictive regulations, efforts to improve cannabis packaging are underway. Both large- and small-scale producers have been working to reduce the impact of plastics.

Execs at Nova Scotia’s Aqualitas knew cannabis packaging was a problem but found initially found themselves at an impasse as to how to reduce their packaging-related carbon footprint. Even just navigating the bureaucracy around getting their licence had proved challenging; figuring out how to improve their packaging from the plastic options available was an additional quandary.

The company used locally-sourced containers for their products, but “there weren’t many alternatives,” Gillis says. So Aqualitas teamed up with US-based supplier Sana Packaging to develop packaging made from reclaimed, ocean-sourced plastics.

“We wanted to be going into this kind of packaging when we started our company, but we couldn’t find any alternatives,” Gillis says. “The licensing process with Health Canada was extremely time-consuming, so there was a lot of trying not to create a new wheel, so to speak.”

But the wheel did indeed require a degree of reinvention.

“It’s been two years in the making to source raw materials, connect with a manufacturer, get the product certified, conduct product impact investigations, and make it work during a pandemic,” Aqualitas director of operations Josh Adler commented when the producer introduced the new packaging in early 2021.

According to Aqualitas, their first packaging order reclaimed 4,000 pounds of plastic waste from the ocean.

“The difference with this packaging is that it’s reclaimed,” Gillis says. “The starting materials are always reclaimed—we’re not taking something from a renewable source and putting it into the waste stream.”

Other producers have found their own solutions. 48North now uses biodegradable cardboard packaging to house their pre-rolls, which are rolled with unbleached papers. The company’s dried flower bags, which often cannot be recycled because of their foil linings, are instead made of cardboard-like materials, drastically reducing the amount of plastic involved.

Other producers are also making efforts to improve their packaging.

When LP giant Auxly launched their Kolab line of vape cartridges, they came in biodegradable boxes (though vape cartridges themselves can’t be recycled). Mood Ring packages their flower in recyclable aluminum tins and their pre-rolls in compostable doob tubes.

The Green Organic Dutchmen packages in glass jars, and recently Avant, producers of the TreeHugger brand, have developed entirely recyclable packaging with biodegradable cellulose interior bags.

But not all LPs have taken steps to mitigate the environmental damage wreaked by plastic waste. Canopy Growth still uses black mylar plastic bags for dried flower products, which persist as an industry standard.

“The bags we have are not recyclable as of today,” admits Caton, “but they are less plastic, and less weight, and all those kinds of things…We like the bags, they are less onerous on the environment overall, and the cannabis maintains the quality attributes we’re looking for.”

Canopy’s approach illustrates what large-scale producers grapple with when it comes to packaging. Many of their Cannabis 2.0 products, like beverages, could be made at scale using sustainable packaging; but when it comes to core flower products, aka the industry’s bread and butter, changes have been sluggish at best.

“There are starting to be options now,” Caton says. “To get a new packaging into our system requires a bit of work, to be able to fit into our operations and the scale we need. I think our ideas and goals are the same [as smaller producers], but in terms of the scale and the product lines we have, it does just require a little bit more time to make sure it can fit and work for us.”

On the flipside, Canopy has been a leader in advocating for consumer recycling, launching a program in partnership with TerraCycle that accepts any and all cannabis packaging consumers return to the store, including items that aren’t traditionally recyclable such as vape cartridges and black plastic containers.

“The moment is ripe to return to a culture of circular economies, aimed at eliminating waste by favouring responsible and continual re-use of resources. If calls from the public and the realities of a changing climate are heeded, we believe it is possible to uphold public health and safety while meaningfully reducing packaging waste.”

McGill researchers

That initiative has now expanded considerably to include many more industry partners, but Caton admits it isn’t a perfect solution.

“I think ideally, you’d want to continue to work to get products in municipalities’ programs, is my opinion on that,” he says. “That being said, until that can take place, having these alternatives are critical,” Caton says.

Since launching that program, over 12 million cannabis packages have been diverted from landfills. Both Canopy and Aqualitas have demonstrated that the industry is not without options in the fight against plastic waste– and that as the industry matures, there is both a will and a way to reduce plastics in the Canadian cannabis industry.

Proposed solutions involve producers, consumers, and legislators

For consumers, packaging issues remain largely out of sight– and consequently out of mind. The plastic problem is not exclusive to the cannabis industry, but consumers may not be educated as to the scope of the issue or what solutions might exist.

Nonetheless, both regulatory experts and industry players are making efforts to minimize their packaging-derived environmental impact.

In their aforementioned report, McGill researchers proposed several measures that could significantly reduce plastic waste. One radical idea? Permit bulk sales: consumers bring a jar to the dispensary, and budtenders weigh out the buyer’s desired amount.

A suggestion more likely to pass regulatory muster in the short term involves removing the requirement for child-resistant packages for all products without active THC in them, including CBD products and flower. As these products contain only inactive THC and are non-intoxicating, this measure seems more likely to appease both industry players and regulators alike.

“Dividing cannabis products based on whether or not they include active THC content could permit the vast majority of products to be sold without child-resistant packaging,” notes the study. Many, like Gillis, want to be able to promote the work they have done on their own packaging– believing that this would create an incentive for consumers to gravitate toward sustainable packaging.

“There’s a huge disconnect when you see the absence of recognition—when companies do good work, when they work with regulators or government, they should be advertising that effort,” says Gillis.

“Give us a sustainable stamp, give us some recognition in the store, mark up the product less than one that doesn’t reflect that value,” she continues. “We try to tell every provincial retailer and distributor about our packaging, and some of them are like ‘eh, so what?’”

Caton agrees that cannabis consumers should have a say in how their purchases are packaged.

Related

Where is growing weed most environmentally sound?

“The community needs to continue to raise these issues up,” he says. “Ideally, you want to make it simple for the consumer.

You’re putting yourself in the shoes of someone who just bought [a product] and wants to feel good about putting it in the recycling bin. I think that’s ultimately where you want to get to, or to biodegradable.”

But ultimately, says Gillis, the bulk of the responsibility for developing and implementing more sustainable packaging solutions lies with the industry.

“Companies have to start making ethical decisions,” she says, “and not just financial decisions, about what they are going to put their product in, because that package is a reflection of who they are as a company.”

Those decisions are long overdue– and as the icebergs melt and the world burns, they must be made now before it’s too late.

Kieran Delamont

Kieran is a writer and photographer based in Nova Scotia, located in Mi’kma’ki, the ancestral and unceded territory of the Mi’kmaq people. His work has appeared in Broadview, The Walrus, Maisonneuve, and elsewhere, and he has been writing about the cannabis industry since 2016.

View Kieran Delamont’s articles

By submitting this form, you will be subscribed to news and promotional emails from Leafly and you agree to Leafly’s Terms of Service and Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe from Leafly email messages anytime.

Post a comment: