Is your drug a psychedelic, a dissociative, or an empathogen?

Mind & Matter is a monthly column by Nick Jikomes, PhD, Leafly’s director of science and innovation.

All intoxicating drugs are psychoactive, but not all psychoactive drugs are intoxicating.

This is often misunderstood by patients, consumers and the mainstream media. In the cannabis world, we hear all the time – wrongly – that THC is psychoactive but CBD is not.

Both drugs are actually psychoactive. At the right dose, CBD can affect mood and have anti-anxiety effects. But of the two, only THC is intoxicating.

Think of it this way: A drug is intoxicating when it interferes with your ability to act and make decisions. Caffeine and SSRIs like Prozac are psychoactive. Alcohol is psychoactive and intoxicating. A good rule of thumb is that when a psychoactive drug interferes with your motor skills, it’s intoxicating.

A psychoactive drug is any chemical substance that causes a measurable change in perception, cognition, mood, consciousness, or behavior compared to placebo. This is a very broad category. It includes everything from the caffeine in your morning coffee to prescription antidepressants or powerful hallucinogens.

But how are further boundaries drawn with all psychoactive drugs?

In science and medicine, structure and function are closely related. Knowing the chemical structure and functional effects of drugs is useful in distinguishing them by their effects and how they are metabolized in the body.

To classify psychiatric drugs more precisely, you need to know two things:

- What is the specific character of its primary subjective effects?

- On which molecular mechanism do these effects depend?

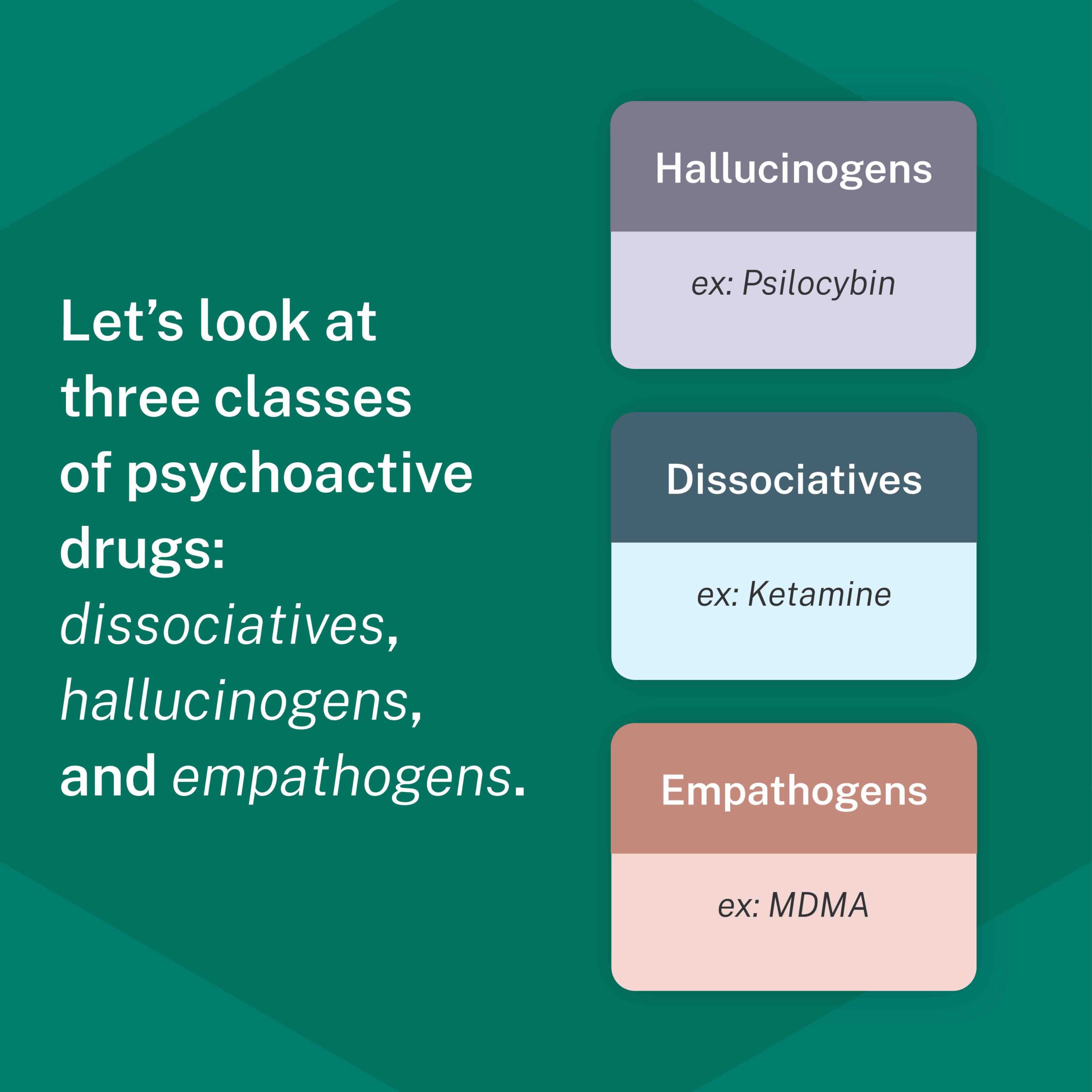

So let’s take a closer look at what distinguishes three classes of psychoactive drugs: dissociatives, hallucinogens, and empathogens. You may know them from their popular role models:

- Dissociative, a class that includes ketamine and nitrous oxide

- Empathogens, including MDMA (ecstasy)

- Hallucinogens, including LSD, psilocybin, ibogaine, and mescaline

Related

Psychedelic Medicine: The Benefits of Psychedelics

Dissociative

Dissociation is a strange and fascinating mental state. You are generally aware of your surroundings, but you feel disconnected from your body and identity.

Ketamine is a good example of a dissociative. At low doses, it can produce rapid antidepressant effects in people with treatment-resistant depression. In higher doses, it produces intoxicating effects not unlike alcohol. Increase the dose and you will develop a dissociative state informally known as “the K-hole”. Go higher and it’s a stunning.

While ketamine has both established and emerging medicinal uses, it is also used in recreational use. Other dissociative drugs are laughing gas (“laughing gas”), PCP (“angel dust”) and dextromethorphan (DXM, a cough suppressant; “robotripping”).

One of the main mechanisms behind their dissociative effects is the ability to block NMDA receptors. This is a specific type of receptor in the brain that is linked to learning, memory, and neuroplasticity. Other types of psychoactive drugs, such as psychedelics, don’t work in this way. Instead, they work through different receptor systems in the brain, which is why they induce different psychoactive effects.

In a recent conversation with psychiatrist and neuroscientist Dr. To Karl Deisseroth he described patients with dissociation:

Empathogens

Empathogens are a class of psychoactive drugs that induce feelings of empathy and emotional openness. Two of the most famous and widely used are MDMA (also known as Ecstasy or Molly) and MDA (also known as Sass). The “A” in their name stands for “amphetamine”, so these drugs have a stimulating effect.

MDMA and MDA both belong to the phenethylamine class. They are chemically similar to psychedelics like mescaline. However, they are not psychedelics in the classical sense as they do not activate serotonin 2A receptors directly. Instead, they cause a temporary increase in the endogenous neurotransmitters serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. While some of their stimulatory and euphoric effects may have largely similar feelings to classic psychedelics, they do not induce hallucinations like psychedelics.

[Tryptamines/Phenethylamines/Classic Psychedelics Graphic]

While MDMA and MDA are known to evoke empathy and an experience with a very positive emotional value, this may have more to do with the social setting in which they are frequently used than with an inevitable effect of the drugs.

For example, some have described them as “non-specific emotional enhancers” capable of enhancing any emotional state one is in. This cannot always lead to a state of “ecstasy”, as Dr. Based on studies, Berra Yazar-Klosinsky has described use of MDMA to treat severe PTSD:

Related

How to dose psychedelic mushrooms

Hallucinogens

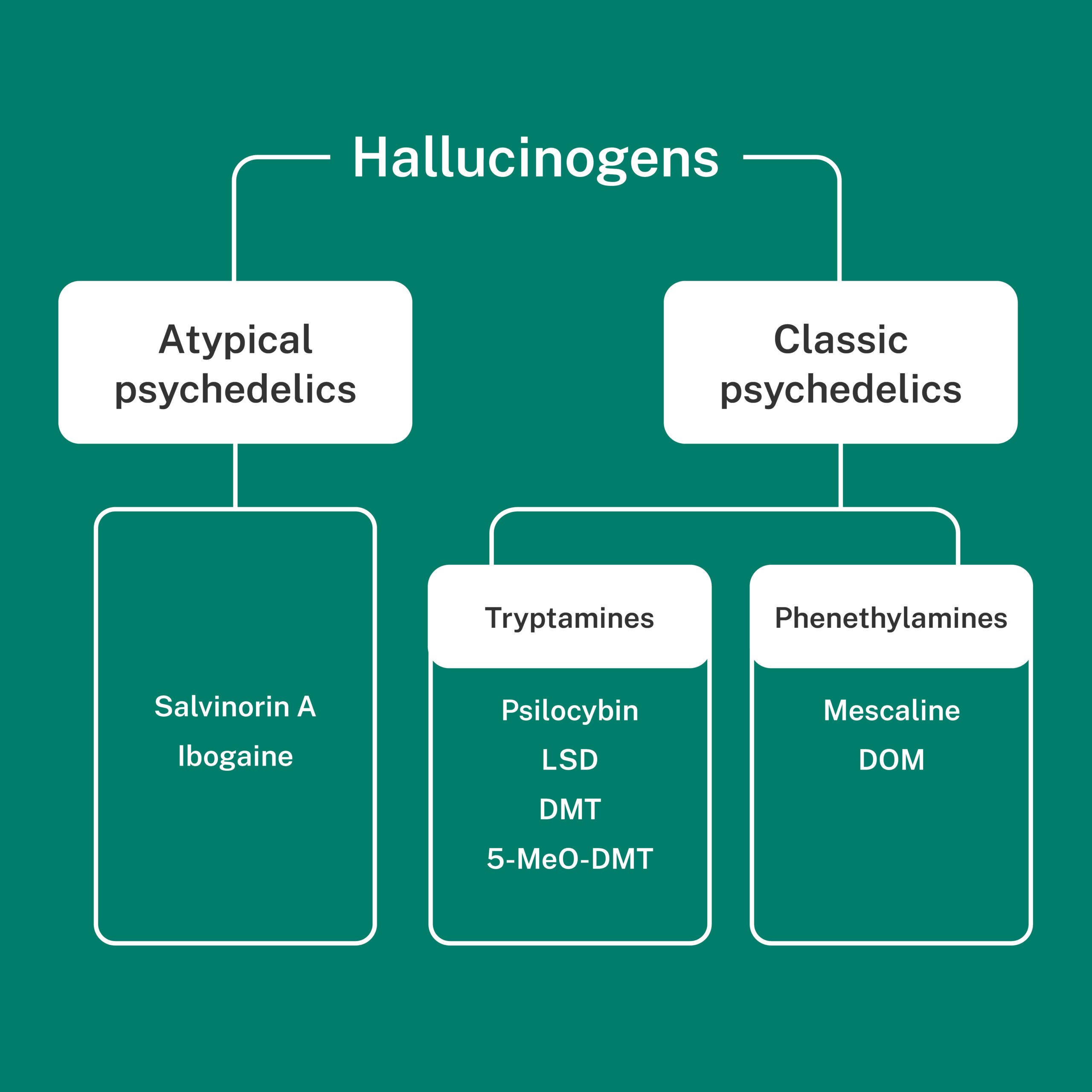

Two types: classic and atypical

Hallucinogens (also called psychedelics) are psychoactive substances that profoundly alter consciousness in a way that involves hallucinations: vivid perceptions that occur without external stimuli.

In other words, they make you perceive things that other people don’t.

At the brighter end of the spectrum, such as a low dose of psilocybin, this can cause colors or geometric patterns to be superimposed on an otherwise normal visual scene.

On the heavier end of the spectrum, such as a high dose of DMT, it can mean immersing yourself in a totalizing hallucinatory experience in which you completely lose touch with consensus reality.

There are two major flavors of hallucinogens: classic psychedelics and atypical psychedelics.

Atypical psychedelics: Ibogaine

Atypical psychedelics trigger hallucinations through other brain receptors. Atypical psychedelics include salvinorin A, the active ingredient in salvia divinorum (an herb mint plant) and ibogaine, which is found in plants such as tabernanthe iboga (a rainforest shrub). While these drugs are interesting, they are typically less popular than classic psychedelics for recreational purposes. That’s because the hallucinations they create are associated with a general feeling of dysphoria, a state of discomfort – the opposite of euphoria.

Classic psychedelics: LSD, psilocybin, mescaline

When someone talks about psychedelics, they usually mean classic psychedelics like LSD, psilocybin, DMT, and mescaline. What they all have in common is their ability to induce hallucinations by activating the serotonin 2A receptor in the brain.

A side note about cannabis: cannabinoids like THC are not considered psychedelics. This is because, within their typical dose range, they do not induce true hallucinations and do not activate serotonin 2A receptors, as is the case with classic psychedelics.

Two classes of hallucinogens

Classic psychedelics (tryptamines & phenethylamines)

Classic psychedelics come in two basic forms, which are defined by their chemical structure:

- Tryptamines – including psilocybin, DMT, and LSD – share a common structure with endogenous compounds like melatonin (a hormone that regulates the sleep cycle) and serotonin (a neurotransmitter that is involved in mood control).

- Phenethylamines – including mescaline and DOI – share a structure with endogenous compounds such as dopamine (a neurotransmitter that is involved in motivation and reward) and adrenaline (a hormone that is involved in the “fight-or-flight” response).

All classic psychedelics induce hallucinations and have the common property of activating the serotonin 2A receptor, but no two have the same effect. This is because each compound stimulates a unique set of brain receptors – sometimes dozens at a time.

Each is also metabolized at a different rate. One psychedelic tryptamine can induce intense hallucinations that last only a few minutes (DMT), while another can induce a psychedelic state that lasts for many hours (LSD).

In general, psychedelic phenethylamines tend to be more stimulant than psychedelic tryptamines. This is due to their structural similarity to endogenous compounds like adrenaline and dopamine, as well as amphetamine-like drugs like MDMA.

The chemistry and subjective effects of psychedelic tryptamines and phenethylamines have been extensively documented by the chemist Alexander Shulgin and his wife Anne. Her books PIHKAL and TIHKAL are often viewed as “the Bible” of psychedelics and other psychoactive drugs.

Phenethylamines: more stimulating effects, like adrenaline

Know your substance, keep experiences positive

The way to think about different types of psychoactive drugs is to ask what general subjective effect they have on consciousness, along with the specific mechanism that drives those effects.

Dissociative drugs induce a state of separation from the body, primarily by blocking NMDA receptors in the brain. Psychedelics reliably induce strong distortions of perception (hallucinations) without external causes. Classic psychedelics accomplish this by activating serotonin 2A receptors instead of serotonin, while atypical psychedelics do this in a different way. Empathogens induce emotional effects not by blocking or activating a specific brain receptor, but by increasing endogenous neurotransmitters.

Knowing what kind of medication is and how it works in the body is important knowledge for everyone who deals with these substances – not just for doctors and scientists.

Arming yourself with this knowledge can help you better understand why psychoactive drug experiences feel like they do, and what the specific risks of a particular drug may be. This can be invigorating, both to enable positive outcomes and to avoid negative ones.

For a deeper look into what makes different psychoactive and psychedelic drugs different, read this or this scientific paper. If you’re having trouble accessing any of the articles, here are some useful tips.

Nick Jikomes, PhD

Nick is the Director of Science & Innovation at Leafly and holds a PhD in Neuroscience from Harvard University and a BS in Genetics from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the host of a popular science podcast which you can listen to for free at www.nickjikomes.com. You can follow him on Twitter: @trikomes

View article by Nick Jikomes, PhD

By submitting this form, you subscribe to Leafly news and promotional emails and agree to Leafly’s Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe from Leafly email messages at any time.

Post a comment: